Virtual Laboratory on Cognitive L2 Pedagogy

Project Objective

The Virtual Laboratory is an international project that is intended for practitioners (L2 teachers), students and researchers in the field of second and foreign language (L2) acquisition, teaching and learning.

The Virtual Laboratory aims to popularize and promote Cognitive L2 Pedagogy, which analyzes and implements educational decisions from the perspective of our knowledge of cognitive architecture, neural and cognitive processes and cognitive structures (representations) involved in language acquisition, learning, and usage. Cognitive L2 Pedagogy relies on cognitive and neurocognitive sciences data applied to L2 acquisition. It is and rooted in the general cognitive conditions-based pedagogical theory that postulates that ‘instructional strategies should facilitate the internal processes of learning’ (Richey, Klein & Tracey, 2011, p. 105). It means that a teacher is responsible to design and conduct classroom activities in a way that maximizes learners’ cognitive ability and facilitates cognitive and neurocognitive processes.

We believe that this knowledge is necessary for L2 instructors to increase professional awareness by developing general principles that can guide methodological decisions in everyday teaching practice in the post-method era.

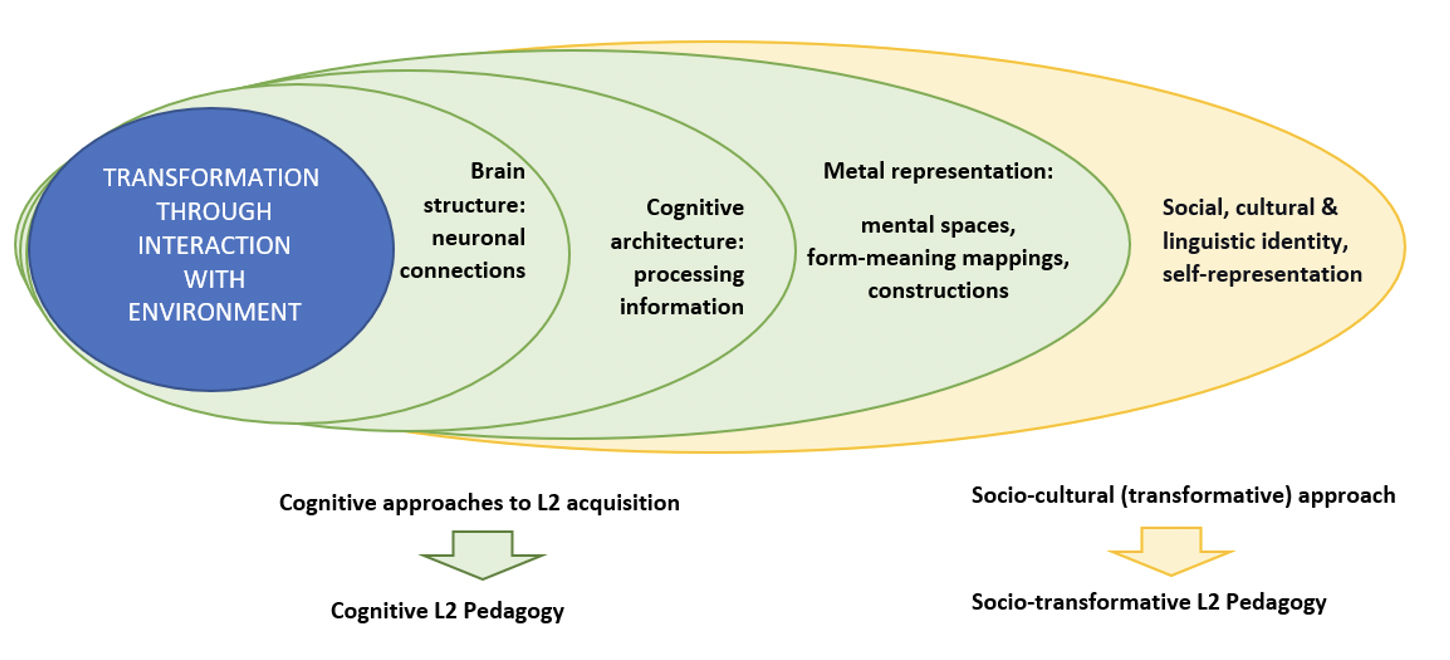

The Virtual Laboratory adopts a wide understanding of the concept ‘cognitive’ which refers to three mutually complementary levels of ‘cognition’ and consequently to three scientific areas:

What is 'Cognitive'? Theoretical Statement

Show/hide details

Cognitive science (cognitive psychology) studies the cognition from the perspective of cognitive architecture and processes which are involved into processing information in the human brain (e.g. perception, encoding, storage, retrieval from memory, meta-cognition, problem-solving, etc.). From cognitive science perspective, learning (including language learning) is as change that a system undergoes to its informational state or processing, for the purpose of more effective future action and in response what the system experiences (Divies, 2017a,b). The most known cognitive processes involved into L2 learning are the those related to:

- the working memory (Baddeley, 2003; Sweller, 1994; Sweller, Ayres, & Kalyuga, 2011) involving phonological (Baddeley, 2003; Baddeley, Papagno, & Vallar, 1988) and grammatical development (Ellis & Sinclair, 1996; Ellis, Lee & Reber, 1999; Robinson, 1997; Williams & Lovatt, 2003),

- attentional functions, awareness and inhibition (Bialystok, 1978; Darcy, Mora, & Daidone, 2016; N. Ellis, 2007; Doughty, 1991; Robinson, 1997; Schmidt, 1993, 1994, 1995; Tomlni & Villa, 1994; VanPatten, 1990, 1996),

- deep (semantic) vs. shallow level of encoding (Craik & Tulving, 1975),

- multi-channel encoding (cf. Duo Channel Coding theory by A. Paivio, 1971, 1986), and

- interface between declarative and non-declarative (procedural) memory (N. Ellis, 2005, 2007; 2008; Paradis, 2004; 2009).

Cognitive neuroscience studies the biological processes that underlie human cognition in regards to the relation between brain structures, activity and cognitive function. It explores, among otherthing, neural (biological) correlates of cognitive processes previously described in the terms of cognitive psychology. Today, neuroscientific data are provided mostly by research conducted using brain imagery. Neuroscientific approaches conceptualize learning (including language learning) through the concept of neuroplasticity, i.e. the capacity of human brain to experience a functional and biochemical (qualitative and qualitative) transformation through developing connections (alias consolidation or engram) between different groups of neurons in response to environmental stimulus, cognitive demand, or behavioral experience (Chai, 2016; Li, Legault, Litcofsky 2014; Costa & Sebastián-Gallés, 2014; Witteman et al., 2018 and others).

- neuroeducation (Mason, 2009; Mareschal, Butterworth, & Tolmie, 2013; Lee & Juan, 2013) which develops general education principles in accordance with neural studies data.

- neurolinguistics (Roberts et al. 2018; N. Ellis, 2008), which deals with specific phenomena related to language acquisition and usage and includes, among others, the neurolinguistic theory of bilingualism (Paradis, 2004; 2009), and the declarative/procedural model of language (Ullman, 2001, 2004, 2015; Ullman & Lovelett, 2018), et.

The tenets of neuroeducation and neurolinguistics rest on the first law of neuroplasticity postulating that ‘‘[Neuronal] сells that fire together wire together'’ (Hebb, 1949, p. 62). From this law, it follows, for example, that the combination of spaced repetition (also known as distributed practice, spaced testing or the spacing effect; i.e. introducing temporal gaps between repeated presentations of the same item) and active retrieval from memory (also known as the memory testing or the testing effect; i.e. retrieving learned information from memory instead of restudying) constitute the most effective techniques for learning, as well as ‘for the retention of language, which is generally the goal of language learning’ (Ullman & Lavelett, p. 56).

Cognitive linguistics is an interdisciplinary branch of linguistics, combining knowledge and research from cognitive psychology, neuropsychology and linguistics, which studies how the language represents the world though conceptualization, alias mental spaces building.

Cognitive linguistics has as its central concern the representation of conceptual structure in language. It thus addresses the linguistic structuring of basic conceptual categories such as space and time, scenes and events, entities and processes, motion and location, and force and causation. To these it adds basic categories of cognition such as attention and perspective, volition and intention, and expectation and affect. It addresses the interrelationships of conceptual structures, such as those in metaphoric mapping, those within a semantic frame, those between text and context, and those in the grouping of conceptual categories into large structuring systems. (Talmy, 2006, p.542)

Thus, cognitive linguistics explains:

how language mutuallу interfaces with conceptual structure as this becomes established during L2 development and as it becomes available for change during L2 development (Robinson & Ellis, 2008, p.3-8)

Cognitive linguistics holds that the basic unit of language representation are constructions, form-meaning mappings conventionalized in the child L1 learner and adult L2 learner speech community.

Today cognitive linguistics is represented by cognitive grammar Langacker, 1987; 2008), constructionist theory of language acquisition and construction grammar (N. Ellis, 1996, Sinclair, 1991, 2004, Tomasello, 2003; Goldberg, 2003), systemic functional linguistics (Halliday, 2013), usage-based linguistics (N. Ellis, 2011, 2019, Wulff & Ellis, 2018), exemplar-based theory (Kaplan, 2017, Pierrehumbert, 2001; Skousen, Lonsdale, Parkinson, 200, Storms, De Boeck, Puts, 2000), cognitive semantics (Talmy, 2000, Slobin 2004), etc.

Why Cognitive Approaches? Educational Statements

Show/hide details

Cognitive L2 pedagogy is rooted in the general cognitive conditions-based pedagogical theory that postulates that:

instructional strategies should facilitate the internal processes of learning (Richey, Klein & Tracey, 2011, p. 105).

It means that a teacher is responsible for designing and conducting classroom activities in a way that maximizes the learner’s cognitive ability and facilitates cognitive and neurocognitive processes.

A wealth of literature explaining the ‘internal processes’ related to L2 acquisition is available today to specialists and the general public. For example, a recently published comprehensive bibliography on working memory and its role in L1 and L2 acquisition (Wen, 2018) comprises more than 3000 publications derived from cognitive and neurocognitive research.

If cognitive approaches still need to be promoted among L2 teachers, it is due to two reasons.

Firstly, cognitive psychology, neurolinguistics and cognitive linguistics applied to L2 learning and teaching constitute an extremely rapidly growing fields of knowledge with a specific conceptual vocabulary. They are not deeply integrated in L2 teachers’ education and require a considerable investment for anyone who wishing to understand and apply them to her L2 teaching practice.

Secondly, over the past twenty years, the development of L2 pedagogy has been impacted by a so-called poststructuralist paradigm (Pavlenko, 2002). This paradigm encompasses a lot of new approaches reconceptualizing the L2 learning process from a sociocultural perspective (Lantolf & Thorne, 2006; Von Lier, 2004) and focusing on different aspects of psychological and identical transformation experienced by L2 learners through interaction with lingo-cultural and social environments. From this ‘socio-transformative’ perspective, the preoccupation with individual (neuro)cognitive aspects of the L2 acquisition has been viewed as not very relevant or even misplaced (Van Lier, 2004).

However, today a new emerging trend claims for a holistic ‘sociocognitive imperative’ in L2 pedagogy. According to the supports of this trend:

highly effective pedagogy requires viewing language and language learning as both cognitive and social phenomena, and that teachers who seek to truly understand their responsibilities do not have the luxury of choosing one perspective over the other. Indeed, the two theoretical approaches generally converge in recommending instructional sequences where teacher modeling and guidance in second language (L2) communication are followed by handover to learners for independent performance (van Lier, 2008). In order to make use of this three-stage process, however, teachers must understand how each theoretical perspective depicts the available options for decision making (Touth & Davin, 2016, p. 149)

The point of epistemological convergence between Cognitive and Socio-transformative L2 Pedagogies can be found in the concept concept of transformation through interaction with the environment itself.

We at the Virtual Laboratory embrace a holistic understanding of the L2 acquisition process as a gradual transformation – cognitive, neuronal, psychological and socio-identical – which happens through interaction with the environment.

From this perspective, our project aims at bridging and reconciling not only Theory and Practice but also Cognitive L2 pedagogy and Socio-transformative L2 pedagogy.

Organizers

The project was initiated by the Institute of Slavic Studies of Heidelberg University and the Cognitive Pedagogy for Language Learning (CPLL) international research group. It is supported financially by the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD). Dr. Maria Bondarenko (Heidelberg University, Germany) is a responsible for the project (research, instructional design, moderation). Dr. Vita Kogan (University of Kent, UK) is a scientific advisor and assistant.

General Framework of the Project

The virtual laboratory (a MOOC-like resource) constitutes an open collection of recorded videoconferences where recognized experts in the field of L2 acquisition, learning and teaching share their ideas and findings on a topic and in a format of their choice.

We encourage any format of your choice, including but not limited to:

- a conference (traditional lecture) with or without slides;

- an interview;

- a peer discussion / roundtable;

- a workshop.

The videos are to be recorded with the help of online communication technology (ZOOM and heiCONF) and they will be made available online as Learning Units. The recorded videoconferences will be available on the project webspace. They will be accompanied by reflective activities for deeper comprehension and by suggestions for further reading.

Guest Lectures

- 01.08.2022, Dr. Olessya Kisselev, Kurs: Didaktik des Russischen als Fremdsprache: vom Poststrukturalismus über den Kognitivismus hin zum technologiegestützten Unterricht, Russian heritage language pedagogy: research-based account and teaching practice

- 26.09.2020, Prof. Irene Krasner (Defense Language Institute Foreign Language Center, USA), The Role of Attention in Second Language Acquisition

- 10.09.2020, Dr. Dorothee Kohl-Dietrich, A Cognitive Approach to L2 instruction: Transferring Theory into Teaching Practice

- 24.08.2020 (pre-recorded), Dr. Mohammad Javad Ahmadian, EXPLICIT AND IMPLICIT INSTRUCTION OF REFUSAL STRATEGIES: does working memory capacity play a role?

- 11.08.2020, Sapna Sehgal (University of Barcelona, Ph.D. Candidate; Research directors: Prof. Dr. Joan C. Mora & Prof. Dr. Raquel Serrano), Cognitive factors of L2 Oral Fluency Development Cognitive fluency and Inhibitory Control in American English learners of Spanish Studying Abroad

- 08.08.2020, Ass. Prof. Dr. Richard Pinner (Sophia University, Tokyo, Japan), Authenticity and Metacognition in L2 Learning

- 02.08.2020, Prof. Dr. Betty Lou Leaver (former Provost of the Defense Language Institute Foreign Language Center, USA), Cognitive distortions in L2 acquisition: What are they, how to recognize them, what to do about them

- 16.07.2020, Prof. Dr. Michael Ullman (Georgetown University, USA, Department of Neuroscience), How understanding the neurocognition of language can help us improve second language learning and pedagogy

- 09.07.2020, Dr. Vita Kogan (University of Kent, UK), Gamification of L2 Instruction: Cognitive Impact

- 08.07.2020, Михаила Сухотина и Леонида Тишкова, «Великаны» (1985) Михаила Сухотина 35 лет спустя: Взгляд авторов на историю создания и актуальное прочтение

Copyrights

All copyrights are held by the presenter, and references to the videoconferences will be required just as if it were a reference a reference to a conference paper.

Topics

We welcome contributions on any of the following topics related to cognitive, neurocognitive, neurolinguistic and cognitive linguistic perspectives:

- theoretical reflections and research on human cognition in connection to language acquisition which have the potential to reinforce L2 teaching practice;

- case studies of specific teaching practice (an approach, an instructional strategy, instructional design principles, etc.) reviewed from the perspectives of cognitive sciences;

- case studies on teaching a specific linguistic material (e.g. nom-adjective agreements, verbal tenses, aspects, grammatical cases, phonetics, syntax, etc.) in a specific language reviewed from the perspectives of cognitive and neurocognitive sciences, neurolinguistics and cognitive linguistics.

Contact Information

If you are interested in presenting a talk within the Virtual Laboratory, or in any other form of collaboration, please contact:

Dr. Maria Bondarenko

maria.bondarenko@slav.uni-heridelberg.de

Bibliography

Bialystok, E. (1978). A theoretical model of second language learning, Language Learning, 28(1), 69-83.

Baddeley, A. (2003). Working Memory and Language: An Overview, Journal of Communication Disorders 36(3), 189-208.

Baddeley, A., Papagno, C., & Vallar, G. (1988). When long-term learning depends on short-term storage. Journal of memory and language, 27(5), 586-595.

Chai, X. J., Berken, J. A., Barbeau, E. B., Soles, J., Callahan, M., Chen, J.K., et al. (2016). Intrinsic functional connectivity in the adult brain and success in second-language learning. Journal of Neuroscience, 36, 755–761.

Costa, A., & Sebastián-Gallés, N. (2014). How does the bilingual experience sculpt the brain? Natural Reviews Neuroscience, 15, 336–345.

Craik, R.I.M, & Tulving, E. (1975). Depth of Processing and the Retention of Words in Episodic Memory, Journal of Experimental Psychology, 104 (3), 268-294.

Darcy, I., Mora, J. C., & Daidone, D. (2016). The role of inhibitory control in second language phonological processing. Language Learning, 66(4), 741-773.

Davies, J. (2017a). What is learning? A definition for cognitive science. In G. Gunzelmann, A. Howes, T. Tenbrink, & E. J. Davelaar (Eds.), Proceedings of the 39th Annual Conference of the Cognitive Science Society (pp. 271-276). Austin, TX: Cognitive Science Society.

Davies, J. (2017b). What is learning? A Definition of cognitive sciences. Academic-style talk based on the above paper.

Doughty, C. (1991). Second language instruction does make a difference: Evidence from an empirical study of SL relativization. Studies in second language acquisition, 13(4), 431-469.

Hebb, D. (1949). The Organization of Behaviour. John Wiley & Sons.

Hickok, G. & Small, S.L. (Eds.) (2015) Neurobiology of Language, Academic Press: lsevier.

Lantolf, J. P., & Thorne, S. L. (2006). Sociocultural theory and the genesis of second language development. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lee, H.W, & Juan, C.H. (2013). What can cognitive neuroscience do to enhance our understanding of education and learning? Journal of Neuroscience and Neuroengineering, 2 (4), 393-399.

Li, P., Legault, J., Litcofsky, K.A. (2014). Neuroplasticity as a function of second language learning: Anatomical changes in the human brain, Cortex, 58, 301-324.

Mareschal, D., Butterworth, B. & Tolmie, A. (2013). Educational Neuroscience. Oxford, UK: Wiley-Blackwell.

Mason, L. (2009). Bridging neuroscience and education: A two-way path is possible. Cortex, 45(4), 548-549.

Ellis, N. C. (1996). Sequencing in SLA: Phonological Memory, Chunking and Points of Order. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 18, 91-126.

Ellis, N.C. (2005). At the interface: Dynamic interactions of explicit and implicit language knowledge. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 27, 305-352.

Ellis, N.C. (2007). The Weak-Interface, Consciousness, and Form-focussed instruction: Mind the Doors. In S. Fotos & H. Nassaji (Eds.), Form Focused Instruction and Teacher Education: Studies in Honour of Rod Ellis (pp. 17-33), Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ellis, N.C. (2008). The Psycholinguistics of the Interaction Hypothesis. In A. Mackey and C. Polio (Eds.), Multiple Perspectives on Interaction in SLA: Second language research in Honor of Susan M. Gass (pp. 11-40). New York: Routledge.

Ellis, N.C. (2011). The emergence of language as a Complex Adaptive System. Simpson, J. (Ed.). Routledge Handbook of Applied Linguistics. pp. 666–679.

Ellis, N.C. (2019). Usage-based theories of Construction Grammar: Triangulating Corpus Linguistics and Psycholinguistics. J. Egbert & P. Baker (Eds.), Using Corpus Methods to Triangulate Linguistic Analysis (pp. 239-267). New York & London: Routledge.

Ellis, N.C., Lee, M.W., & Reber, A.R. (1999). Phonological working memory in artificial language acquisition. Manuscript in preparation, University of Wales, Bangor.

Ellis, N.C. & Sinclair, S. G. (1996). Working memory in the acquisition of vocabulary and syntax: Putting language in good order. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 49(1), 234-250.

Goldberg, Adele E. (2003). Constructions: a new theoretical approach to language, Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 7(5), 219-224.

Kaplan, Abbe (2017). Exemplar-Based Models in Linguistics. obo in Linguistics. doi: 10.1093/obo/9780199772810-0201.

Langacker, R. (1987) Foundations of Cognitive Grammar, Volume I, Theoretical Prerequisites. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press.

Langacker, R. (2008) Cognitive Grammar: A Basic Introduction. New Yourk: Oxford University Press.

Paivio, A (1971). Imagery and verbal processes. New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston.

Paivio, A (1986). Mental representations: a dual coding approach. Oxford. England: Oxford University Press.

Paradis, M. (2004). A neurolinguistic theory of bilingualism. Amsterdam / Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Paradis, M. (2009). Declarative and procedural determinants of second languages. Amsterdam / Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Pavlenko, A. (2002). Poststructuralist approaches to the study of social factors in second language learning and use. In: V. Cook (ed.) Portraits of the L2 user. (pp. 277-302). Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Pierrehumbert, J. (2001). Exemplar dynamics: word frequency, lenition, and contrast. J. Bybee, & P. Hopper (Eds.), Frequency effects and the emergence of linguistic structure (pp. 137-157), Amsterdam: John Benjamins

Robinson, P., Ellis, N. (Eds.) (2008). Handbook of Cognitive Linguistics and Second Language Acquisition. Routledge.

Robinson, P. (1997). Individual differences and the fundamental similarity of implicit and explicit adult second language learning. Language learning, 47(1), 45-99.

Schmidt, R. (1993). Awareness and second language acquisition. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 13, 206-226.

Schmidt, R. (1994). Deconstructing consciousness in search if useful definitions for allied linguistics. AILA Review, 11, 11-26.

Schmidt, R. (1995). Consciousness and foreign language learning: A tutorial on the role of attention and awareness in learning. In Schmidt R. (Ed.), Attention and awareness in foreign language learning (pp. 1-63). Honolulu: University of Hawaii.

Sinclair, J. (Ed.) (1991). Corpus, Concordance, Collocation. Oxford, UK Oxford University Press.

Sinclair, J. (Ed.) (2004). Trust The Text: Language, Corpus and Discourse. London: Routledge.

Skousen, R., Lonsdale, D., & Parkinson, D.B. (Eds.) (2002). An exemplar-based approach to language. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benkamins.

Slobin D. (2004). The many ways to search for a frog: Linguistic typology and the expression of motion events. S. Strömqvist & L. Verhoeven (Eds.) (2004), Relating events in narrative: Vol. 2. Typological and contextual perspectives (pp. 219-257).

Storms, G., De Boeck, P., & Ruts, W. (2000). Prototype and exemplar-based information in natural language categories. Journal of Memory and Language, 42, 51–73.

Sweller, J., Ayres, P., Kalyuga, S. (2011). Cognitive load theory, Spingler.

Talmy, L. (2000). Toward a Cognitive Semantics: Vol. II: Typology and Process in Concept Structuring. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Talmy, L. (2006). Cognitive Linguistics, Encyclopedia of Language & Linguistics (Second Edition) (pp.542-546).

Tomasello, M. (2003). Constructing a Language: A Usage-Based Theory of Language Acquisition, Harvard University Press.

Tomlin, R.S., & Villa, V. (1994). Attention in cognitive science and second language acquisition. Studies in second language acquisition, 16(2), 183-203.

Touth, P.D., & Davin, K.J. (2016). The Sociocognitive Imperative of L2 Pedagogy, The Modern Language Journal, 100, 148-168.

Ullman, M. T. (2001). A neurocognitive perspective on language: The declarative/procedural model. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 2, 717–726

Ullman M.T. (2004). Contributions of memory circuits to language: The declarative/procedural model. Cognition 92, 231–70.

Ullman, M.T. (2015). The Declarative/Procedural Model: A Neurobiological Model of Language Learning, Knowledge, and Use, In: G. Hickok & S.L. Small (Eds.) Neurobiology of Language, (pp. 953-968). Academic Press: lsevier.

Ullman, M.T., & Lovelett, J.T. (2018). Implications of the declarative/procedural model for improving second language learning: The role of memory enhancement techniques. Second Language Research, 34(1), 39-65.

Van Lier, L. (2004). Ecology and Semiotics of Language Learning. A Sociocultural Perspective . Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

VanPatten, B. (1990). Attending to form and content in the input: An experiment in consciousness. Studies in second language acquisition, 12(3), 287-301.

VanPatten, B. (1996). Input processing and grammar instruction in second language acquisition. Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

Williams, J. N., & Lovatt, P. (2003). Phonological memory and rule learning. Language Learning, 53(1), 67-121.

Witteman, J., Chen, Y., Pablos-Robles, L., Parafita Couto, M. C., Wong, P., & Schiller, N. O. (2018). Editorial: (Pushing) the Limits of Neuroplasticity Induced by Adult Language Acquisition. Frontiers in psychology, 9, 1806.

|

|

|

|